Koan for Kini Collins

Kini Collins paints pretty unicorns. They canter over emerald fields, pink manes in the wind, hooves striking silver sparks from the stones.

Kini Collins paints pretty unicorns. They canter over emerald fields, pink manes in the wind, hooves striking silver sparks from the stones.In fact, she doesn’t. But if she did, if they started showing up in her work, she hopes they'd be welcome. "If I see something I'm doing that disturbs me, that I didn't know was in me," Kini says, "I want to keep doing it. If I start painting pink unicorns, I hope I'll continue, even if it grosses me out."

Last year, Kini decided she'd spent enough energy trying to promote and sell her work—her paintings and sculpture. She stopped submitting to shows, pulled her work from the galleries that represented her, and quit attempting to make a living from art. Now, she only sells her art directly out of her studio, and she sells it for the aggregate cost of her materials, calculating the total amount it takes to make her work and then dividing that

by the number of pieces she has. Last time she invited buyers to her studio, she sold her paintings for 35 dollars each.

by the number of pieces she has. Last time she invited buyers to her studio, she sold her paintings for 35 dollars each.Though she isn't sure this has had an effect on what she paints, she feels the liberation of her decision. "I don't feel like I have to repeat myself to satisfy a gallery or the market. I know that whatever I'm making, I'm being true to myself."

The challenge for any artist is to keep on compass, to find the still point of their creative life and make sure that, among the business of art, the art stays central. For Kini, this challenge is paramount, and one she keeps mindful at all times. The moral content of her work is, as she says, as important as the aesthetic. In fact, they're much the same thing.

Kini's paintings are spare, economical. The colors tend to be muted and the forms simplified. There is a solitude about them and a strong contemplative bent. She's fond of birds, pigeons and sparrows and the red knot, which gathers each spring on a beach in

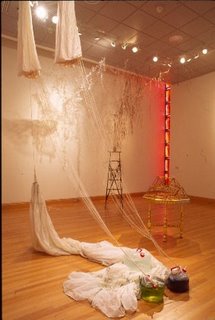

Kini's paintings are spare, economical. The colors tend to be muted and the forms simplified. There is a solitude about them and a strong contemplative bent. She's fond of birds, pigeons and sparrows and the red knot, which gathers each spring on a beach in Also interesting is the stillness that envelops the birds. Kini sculpts pigeons and sparrows out of wire mesh and plaster, perching them on rough blocks of wood. The nervous energy usually associated with birds is quieted, and there is a turned-inward quality, the wings and eyes calm and restful.

"What I like to do," Kini says, "is find the essence of something and see if it fits inside my integrity sphere, whether it resonates with me emotionally, morally, and physically." This search

for the essence of things takes Kini within herself, to look for the center spot, the quintessence of a bird or a patch of weeds, and contemplate its stillness whatever movement it may typically show on the outside. The result is a kind of tension between the physicality of the subject and the meditative essence she looks for.

for the essence of things takes Kini within herself, to look for the center spot, the quintessence of a bird or a patch of weeds, and contemplate its stillness whatever movement it may typically show on the outside. The result is a kind of tension between the physicality of the subject and the meditative essence she looks for.For many years, Kini practiced martial arts, moving for a time to

The materials Kini uses in her art—thick applications of paint, wax, sand, plaster, charcoal—and her love of laboring

over those materials give a strong corporality to the work. As she says, "There's always a lot more in my painting than ends up there. I put a whole bunch of stuff down and then subtract from it." The physical act of painting is thus as important to her as the final product. Interesting then that this art of subtraction, physical as it is, results in a paradoxic stillness too, a hard-won mindfulness that is very much of the mind.

over those materials give a strong corporality to the work. As she says, "There's always a lot more in my painting than ends up there. I put a whole bunch of stuff down and then subtract from it." The physical act of painting is thus as important to her as the final product. Interesting then that this art of subtraction, physical as it is, results in a paradoxic stillness too, a hard-won mindfulness that is very much of the mind.Far from troubling her though, Kini enjoys these kinds of paradoxes and seeks them out. On the one hand, she speaks of the inward quality of her art, how her birds and cityscapes are always some reflection of her thoughts. Later, she tells me that her spine series, elongated depictions of backbones in paint and wax, are the only truly personal work she has done, reflecting her struggles with disc degeneration. The apparent contradictions here do not seem to bother her, probably because both are true in their own context. For Kini, the tension betw

een two seemingly opposing ideas makes for a greater truth, one more complex and hard won. "The next incarnation of humans," she says, "if there is to be one, will live comfortably with paradox."

een two seemingly opposing ideas makes for a greater truth, one more complex and hard won. "The next incarnation of humans," she says, "if there is to be one, will live comfortably with paradox."That attraction to the hard won, the struggled for, is the same attraction she has to her subjects. Kini likes pigeons, sparrows, because they are the underdogs of the bird world, the neglected and sometimes despised, who nevertheless scratch out a good living among the streets and dirty buildings of the city. "These are working-class birds!" she says, pleased with the idea. They fit within the sphere of her integrity, the still point of her contemplation, as well as the scrappy physicality of work and the urban landscape. No pink unicorns, these city birds, though maybe one day they'll join them on verdant pastures.